Uncertainty surrounds the halls of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools as leaders wrestle with how artificial intelligence policy in education should fit into classrooms.

Students face a future where machines handle more than simple tasks, and traditional jobs are in flux.

Superintendent Crystal Hill assessed the stakes bluntly. “The reality is, when they graduate and they leave us, employers are going to be saying, ‘use it, use it, use it.’”

The district has taken a national stage in its approach, choosing 30 campuses as early adopters to experiment with using artificial intelligence alongside teachers and students.

Rebecca Lehtinen, executive director of educational technology, argued there is still a place for classic learning: “We still want our students to develop those critical thinking skills, creative thinking skills and not use AI to potentially just create content, but to enhance their learning.”

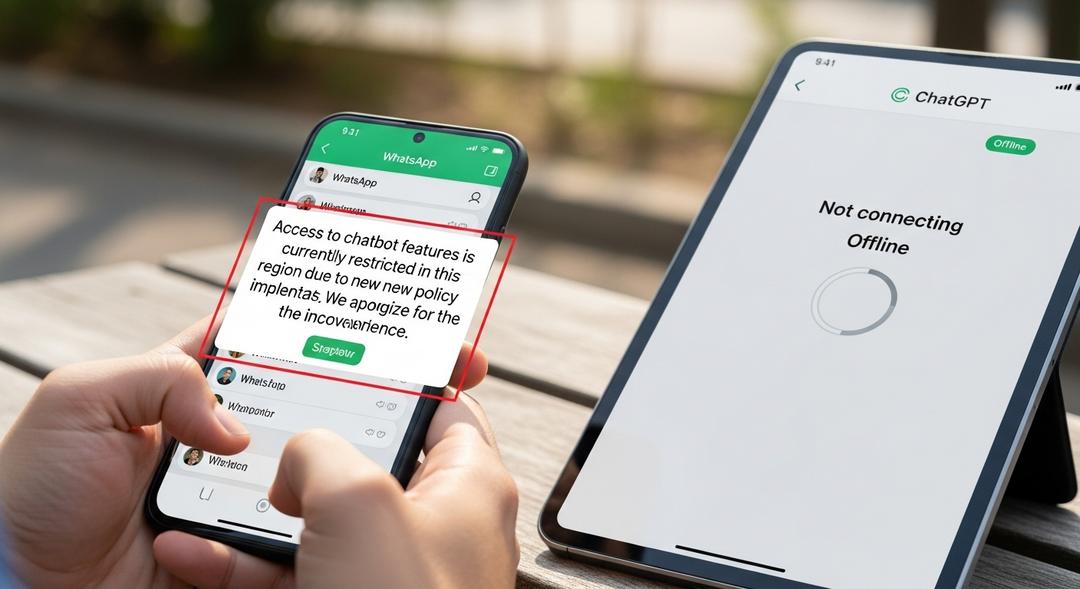

Yet at the same time, district internet filters block powerful platforms like ChatGPT. By next year, the ban will extend to teachers’ devices as well.

Data privacy worries are fueling this caution. Staff may not realize entering a student’s name or ID into a chatbot could be a problem, so the district is rolling out new cybersecurity training.

Balancing Innovation and Oversight

Meanwhile, more than 60 percent of school administrators and nearly half the staff report having used artificial intelligence at work.

CMS sees the upside. Grading, lesson planning, and other routine tasks could all be streamlined, allowing educators to invest more attention directly into students.

To create safer guardrails, the district is considering closed systems like Google’s Gemini, which could allow experimentation with fewer data risks.

The focus remains on finding the “appropriate use” for these tools, Hill said, like having students leverage AI to draft a report but still expecting them to present their findings themselves.

She’s also coining new language for this next era — describing a goal of nurturing a “pro-social classroom,” where connection, empathy, and communication stay at the center of learning.

On concerns about cheating, Hill is unsparing. “You’re always going to find a way to cheat … That’s not an AI issue. That’s a character issue.”

Tens of thousands weighed in when CMS surveyed families and staff ahead of drafting its artificial intelligence blueprint.

Candace Salmon-Hosey, chief technology officer, remembers the atmosphere as “a mixture of scared and curious, just like we all are, because this is uncharted territory, and especially for public school systems.”

Administrators plan to create a guidance document later this summer that sets boundaries on when students and staff are allowed to use artificial intelligence and when they cannot.

A formal guidance on early AI education in schools may soon follow.